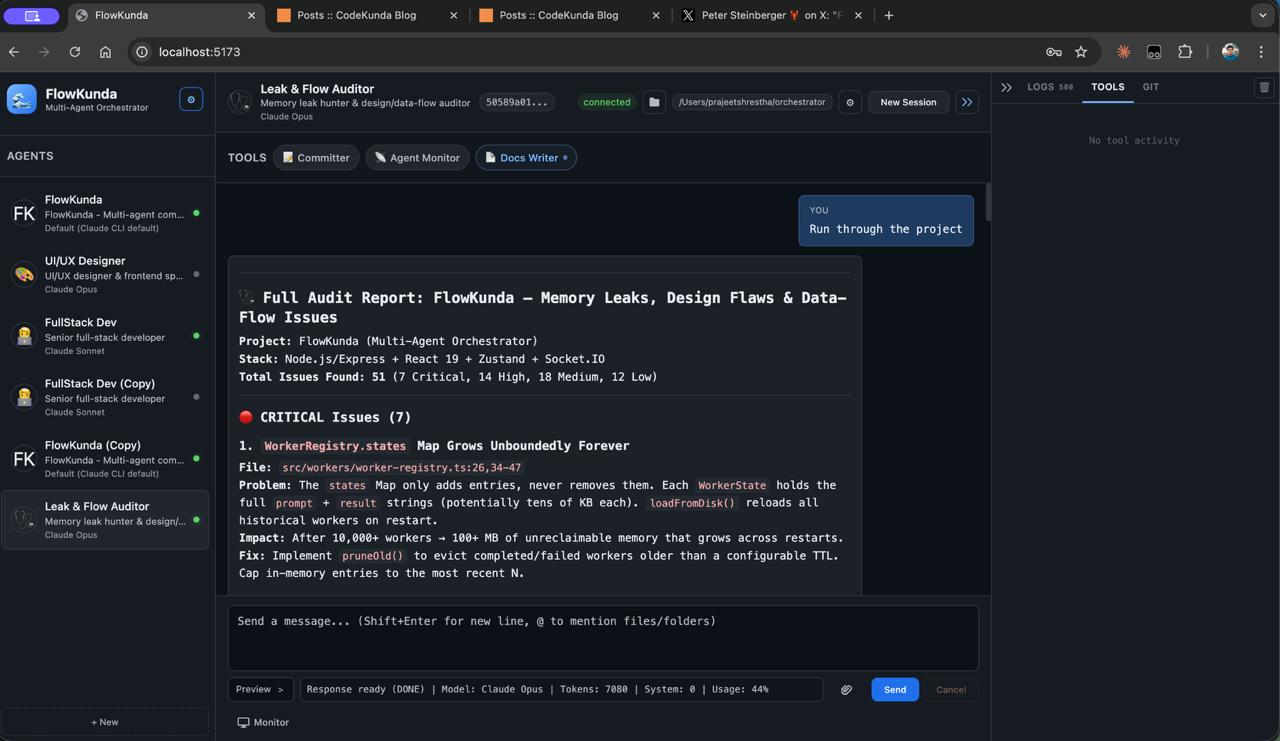

FlowKunda v0.0.3: How a Weekend Hack Became a Production Platform

Three versions. Five days. Nearly 19,000 lines of TypeScript. What started as a frustrated afternoon building a CLI wrapper became something I didn’t expect — a genuine platform.

This is the story of how FlowKunda evolved, told through its architecture.

Day One: The Accidental Architecture (v0.0.1)#

The original problem was embarrassingly simple: I wanted to talk to Claude and Codex at the same time without juggling terminal tabs.

The first version was a bet on one key architectural decision — spawn CLI processes, not API calls. Instead of managing tokens, rate limits, and SDK versions, the system would control the actual CLI tools directly. Every agent gets its own child process. If it crashes, nothing else dies. If the CLI gets an update, the orchestrator gets it for free.

This isn’t how most AI tools work. Most pipe everything through API tokens with artificial constraints baked in. The Orchestrator went the other direction: give each agent the full, unrestricted power of the CLI and get out of the way.

The first architecture was simple:

- A Socket.IO server accepting chat messages

- A process spawner that boots Claude or Codex with the right flags

- A streaming parser that buffers NDJSON chunks from stdout and emits tokens in real-time

- Five isolated Zustand stores on the frontend to prevent cascading re-renders during streaming

That last point turned out to be critical. When tokens arrive 10–50 times per second, a shared state store will destroy your frame rate. Isolating the progress store from the sidebar and log stores was one of those decisions that looked like over-engineering at first and saved the project later.

The frontend started as vanilla JavaScript and was rewritten to React + Vite + Tailwind in a single commit — the most intense two hours of the entire build. But it was the right call. The streaming pipeline needed proper state management, and fighting the DOM manually wasn’t going to scale.

v0.0.1 shipped with 12 commits, 7,570 lines of code, and a hybrid architecture I’m still proud of: one codebase that runs as both an MCP stdio server (so Claude can orchestrate other agents) and an HTTP/WebSocket server (for the browser UI). Zero code duplication between the two entry points.

The First Real Architecture Shift (v0.0.2)#

v0.0.1 proved the concept. v0.0.2 had to prove it could grow.

The biggest change was invisible to the user: migrating from direct process spawning to the Codex App Server architecture. Instead of spawning a new CLI process per message and parsing its output from temporary files, v0.0.2 introduced a persistent JSON-RPC connection to Codex’s app server. This gave the system proper thread-based conversations, streaming delta events, and structured communication instead of fragile stdout parsing.

For Claude, sessions already worked well through --session-id flags. But Codex sessions were brittle in v0.0.1 — process lifecycle was manual, output parsing was complex, and resuming threads was unreliable. The app server architecture solved all of this in one move.

The other major additions in v0.0.2:

- Rich media support — images could flow through the system, not just text

- Web image uploads — drag and drop images into the chat input

- Telegram integration — real bidirectional messaging, not the experimental routing from v0.0.1

- Session management overhaul — proper persistence, reconnection, and agent switching without losing context

v0.0.2 was 13 commits and set the foundation. But it was still fundamentally a chat interface with some agent management bolted on.

The Platform Leap (v0.0.3)#

v0.0.3 is where the architecture had to answer a harder question: what does a multi-agent command center actually need beyond chat?

53 commits and ~19,000 net new lines later, the answer turned out to be: a lot. The development unfolded in eight distinct phases, each building on the last — a textbook case of emergent architecture.

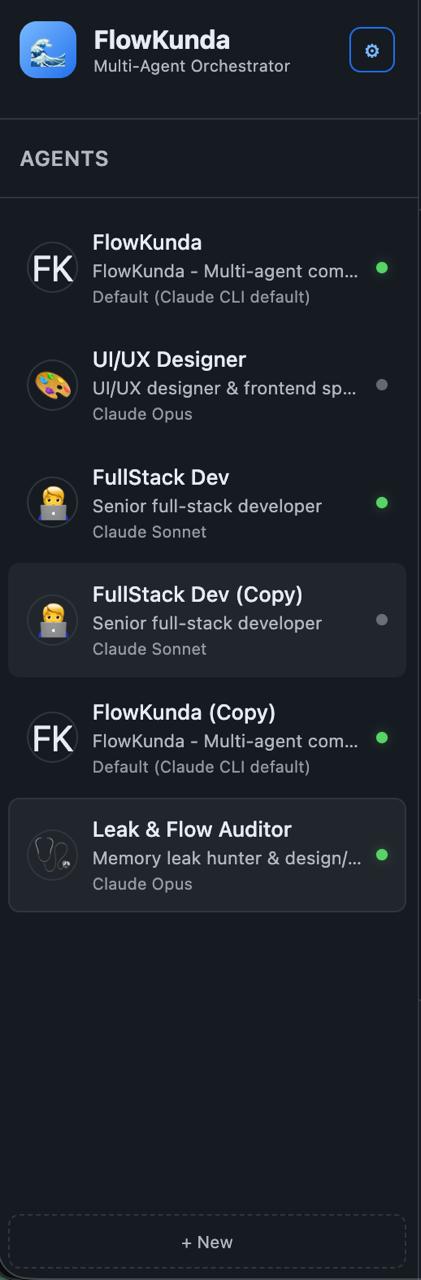

Phase 1: Identity and Configuration#

Before any features, v0.0.3 started with housekeeping. The project got its name — FlowKunda — and with it came a full branding pass across every config, every storage key, every HTML title. More importantly, this phase built the configuration system from scratch.

The config problem was real: FlowKunda needed to run identically across four deployment targets (dev, npm, Docker, SEA binary), each with different filesystem layouts and permission models. The solution is a 4-layer merge — defaults → user config → project config → environment variables — validated at runtime through schema checking. Each layer cleanly overrides the one below it. No special-case code paths for different environments.

This phase also fixed a subtle but important bug: switching agents wasn’t re-injecting personality prompts. The fix was to reset the CLI session on agent switch, ensuring each agent’s character, role, and memory get properly loaded. Small fix, big impact on the multi-agent experience.

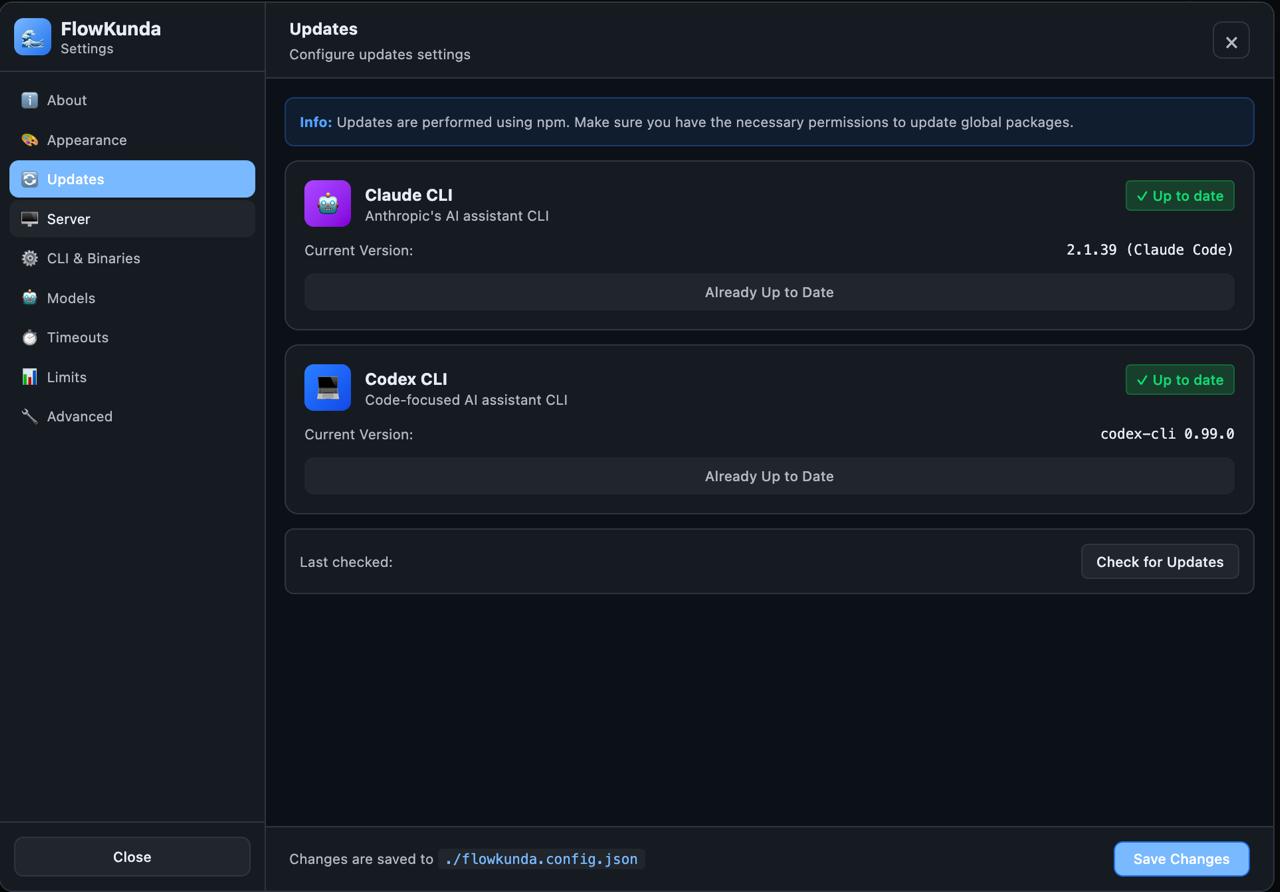

Phase 2: The Distribution Problem#

The single largest commit in the project’s history — over 3,600 lines — tackled distribution. FlowKunda needed to ship as four different artifacts from one codebase:

- Development mode — Vite dev server with hot reload

- npm package — standard Node.js distribution

- Docker image — Alpine-based with a proper init system for signal handling

- SEA binary — a single self-contained executable, zero dependencies

The SEA (Single Executable Application) pipeline bundles the entire application into one binary through a 5-step process: ESBuild bundling with CommonJS interop for ESM modules, blob generation, stub creation, blob injection, and signing. The architectural trick that makes all four targets work without code changes is directory mirroring — the build system ensures the same relative directory structure exists everywhere. Application code always looks in the same relative locations; it’s the build system’s job to put things there.

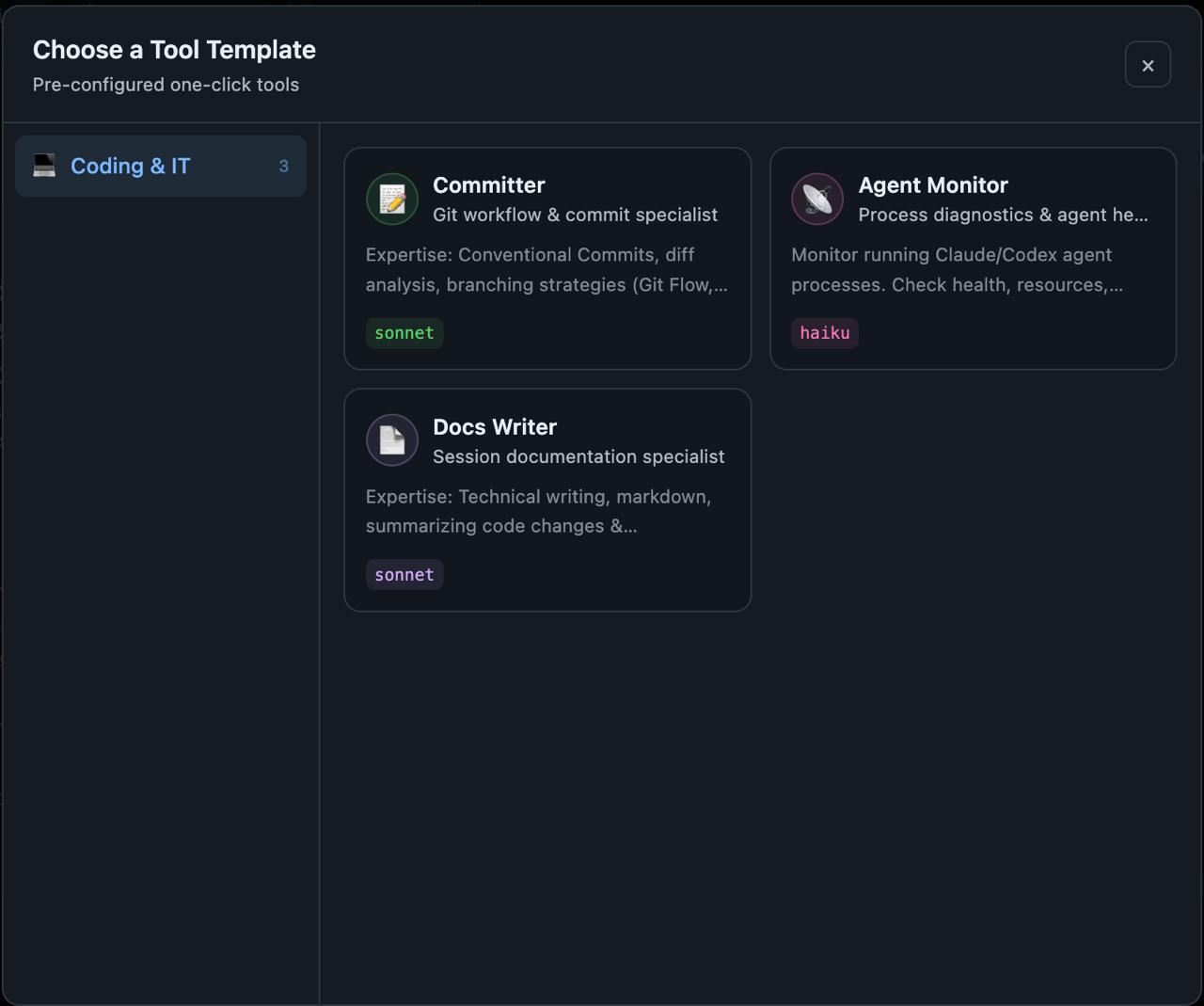

Phase 3: Quick Tools — The First Post-Chat Feature#

This was the inflection point. Up to v0.0.2, FlowKunda was fundamentally a chat application that happened to manage agents. Quick Tools broke that assumption.

The system was built iteratively over 12 commits, and watching the architecture evolve commit-by-commit is instructive:

It started as a template system — browse categories, pick a template, run it. Simple enough. Then came one-click execution with ephemeral agent spawning, where each tool spun up a temporary agent, ran the task, and cleaned up. This worked but felt wasteful.

So ephemeral agents were replaced with persistent, configurable tools supporting two context modes: “none” (stateless execution) and “session” (tools that remember previous runs). This was an important design decision — some tools benefit from memory (like a code reviewer that remembers past feedback), while others should start fresh every time (like a file formatter).

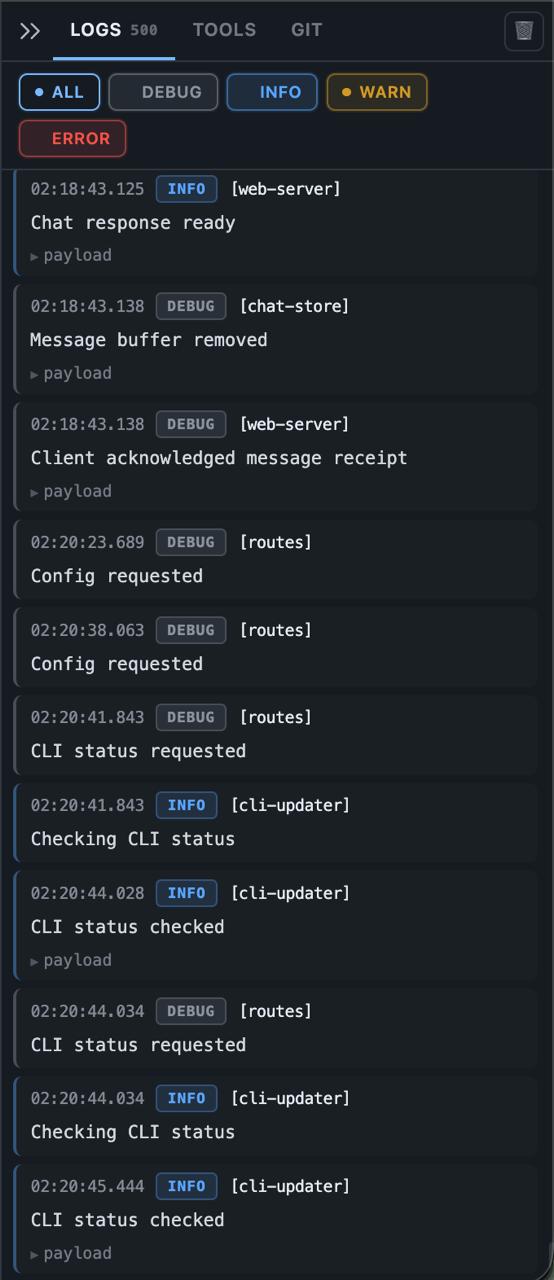

Then came the Tools Panel — a tabbed side panel with its own real-time streaming pipeline, completely independent from the chat stream. The panel maintains a 500-message FIFO buffer to prevent memory growth during long-running tools. This required solving a deduplication problem: tool output needed to appear exclusively in the Tools Panel, never duplicated in chat. Two event streams, one UI, clean separation.

Finally, proper lifecycle management — tools transition through running → completed/failed/cancelled states, with a running pill showing elapsed time and a cancel button. Over 600 lines of architecture documentation captured the final design.

Phase 4: Making the Workspace Visible#

Two features defined this phase, and they share a theme: giving the user visibility into what’s actually happening.

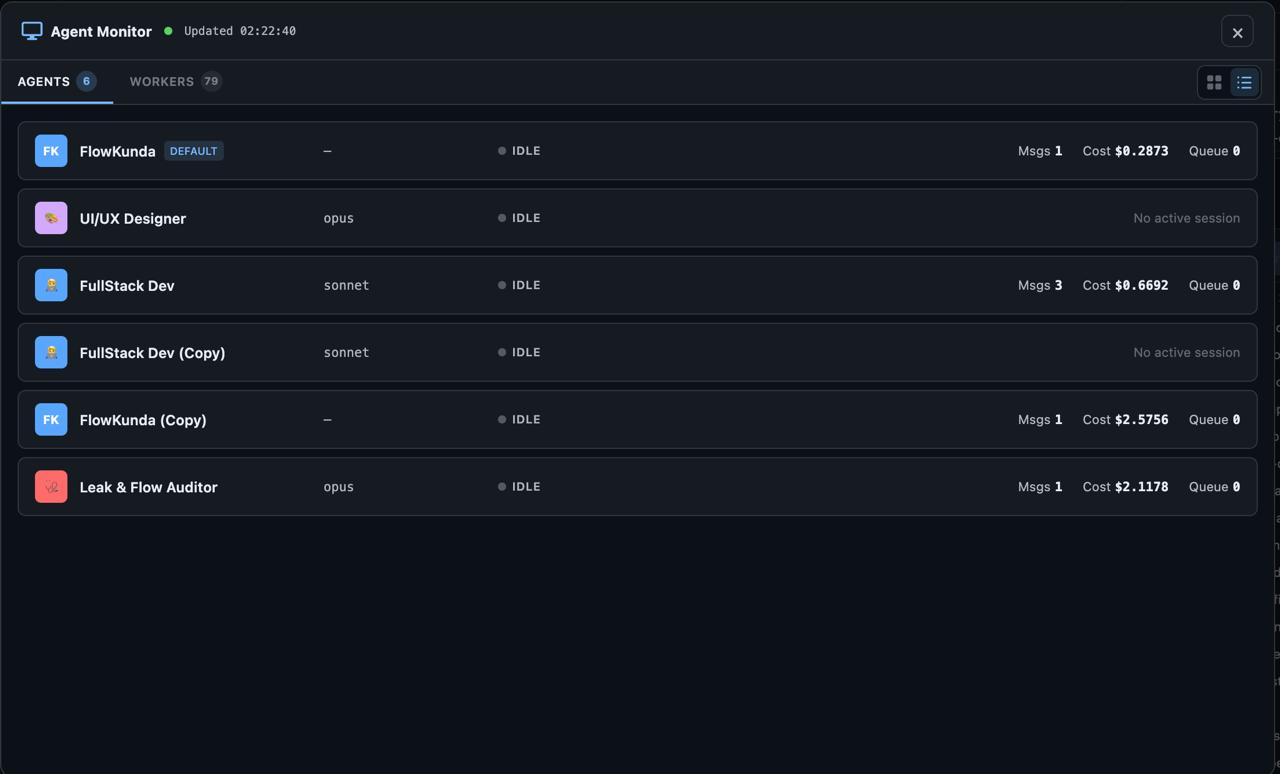

The Agent & Worker Monitor is a full-screen dashboard with its own Socket.IO namespace, polling every 2 seconds, showing every agent’s state, session info, and cost tracking. Grid view for overview, list view for detail. This turned FlowKunda from a tool you interact with into a system you can observe.

The @file mention system lets you type @ in the chat input and fuzzy-search your project files. It discovers files through Git’s index for speed, falls back to directory scanning for non-Git projects, and supports full keyboard navigation. It’s the kind of feature that seems minor until you realize agents need file context constantly, and copy-pasting paths is a terrible workflow.

Phase 5: The Polish Sprint#

Ten commits of pure UI refinement — the kind of work that doesn’t make for exciting architecture diagrams but makes the difference between a prototype and a product.

Agent settings got a proper tabbed interface. The right panel became collapsible with smooth CSS transitions. CLI version management moved into the UI — check for updates and upgrade Claude or Codex without leaving the browser. Chat messages got copy and retry actions on hover. Code blocks got copy buttons. The worker tab got grid/list toggle with localStorage persistence.

The most architecturally interesting addition was the running tool pill — a persistent UI element showing the active tool’s elapsed time with a cancel button. This required wiring the tool lifecycle state (from Phase 3) into a global UI component that persists across panel switches and agent changes. Small surface area, surprisingly tricky plumbing.

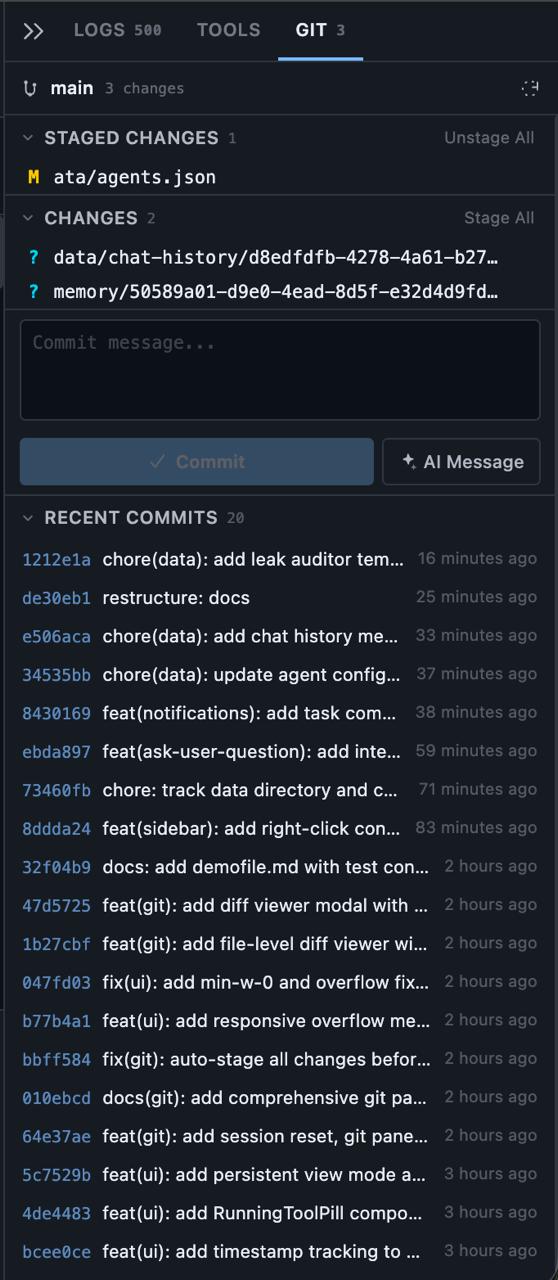

Phase 6: Git Integration#

Seven commits built a complete Git workflow into the browser. This wasn’t wrapping shell commands in buttons — it was building a proper Git client.

The backend exposes 8 REST endpoints covering status, log, diff, staging, and commits. The service layer tracks repository state, generates diffs, and handles stage/unstage operations. The frontend renders file status, provides a commit interface with auto-staging, and — the centerpiece — a full visual diff viewer with side-by-side comparison, syntax highlighting, and the ability to stage or unstage individual files directly from within the diff modal.

This is where the architecture’s child-process model paid off again. Git operations run as isolated processes, so a slow git diff on a massive repo doesn’t block agent conversations or tool execution. Everything stays non-blocking.

The phase also added session reset (/reset command and keyboard shortcut) and agent context menus — small features that emerged from dogfooding the Git workflow and hitting friction points.

Phase 7: Agents That Ask Back#

The most significant architectural addition in v0.0.3 might be AskUserQuestion. Agents can now pause mid-execution and present the user with interactive choices — single-select or multi-select buttons rendered inline in the chat.

This transforms the agent relationship from “fire and forget” to genuinely collaborative. The agent encounters an ambiguity, presents options, you click one, execution continues with your answer injected into the stream.

The implementation required rethinking the streaming pipeline. Previously, data only flowed server→client during a response. Now the stream parser detects tool_use blocks, emits dedicated events, and the client can inject structured answers back into an active stream. The session manager routes responses to the correct waiting agent. Bidirectional flow control in what was designed as a unidirectional pipeline — not trivial.

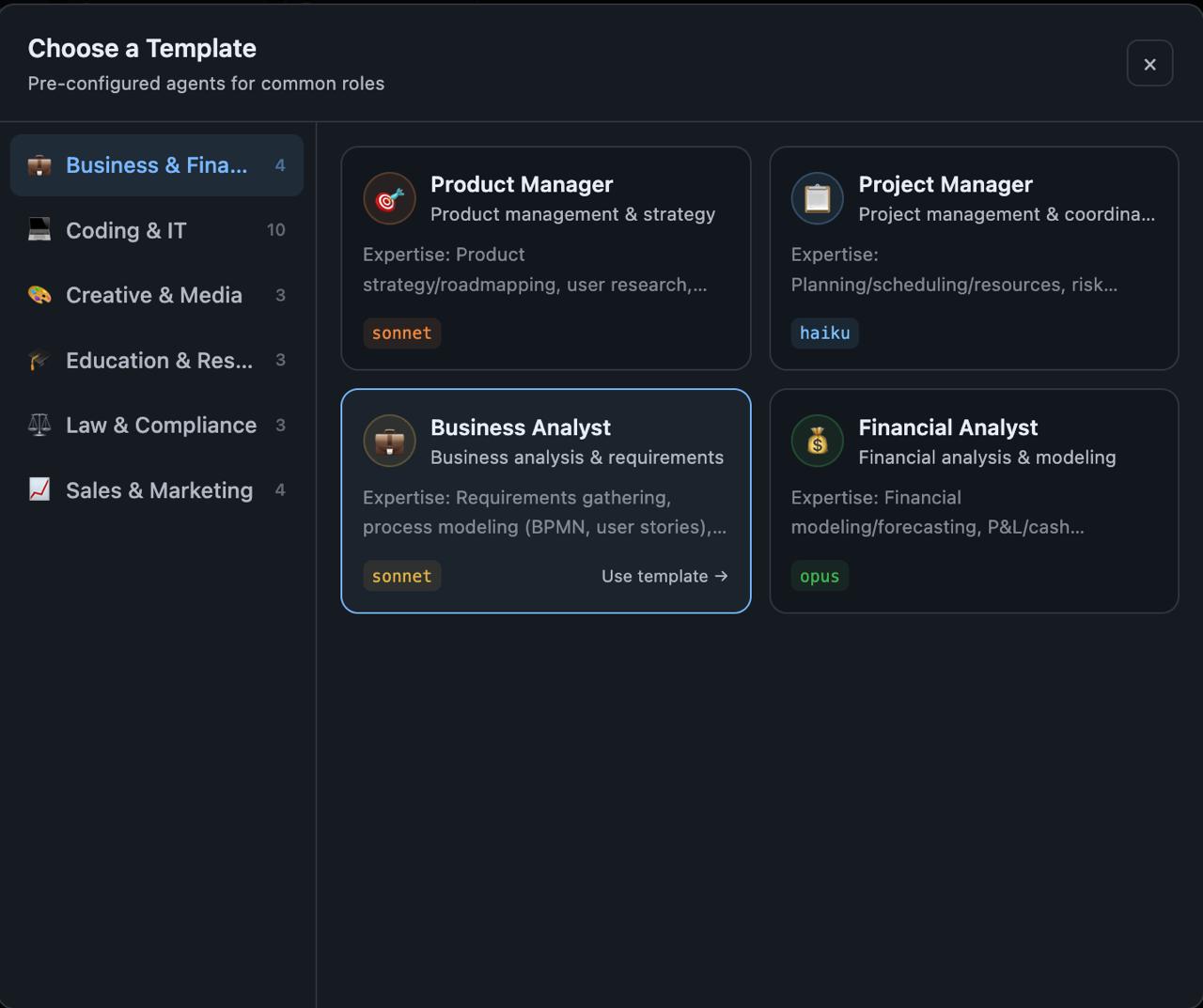

This phase also built the notification system — visual pulsing indicators and configurable sounds (subtle, bell, chime) that fire only when you’re not looking at the active agent. Smart detection prevents notification spam during active conversations. Combined with 30+ agent templates across 6 categories, this phase made FlowKunda feel like a team you’re collaborating with, not a terminal you’re typing into.

Phase 8: Compression and Hardening#

The final commits focused on reducing overhead and ensuring durability. The personality prompt (Soul.md injection) was compressed to cut token usage — a real concern when you’re running multiple agents with persistent sessions. Chat history and agent configurations were moved to tracked storage for persistence across restarts. Worker logging got proper session memory support.

The Architecture Today#

After three releases and eight phases, FlowKunda’s architecture has settled into clear principles:

Process isolation is the foundation. Every agent, worker, Git operation, and tool execution runs in its own process. One crash doesn’t cascade. Scaling means spawning more processes. Each process has a single responsibility.

Stream separation keeps the UI alive. Chat tokens, tool output, Git diffs, monitoring data, and notification events each flow through independent channels with isolated state stores. The frontend subscribes only to what it needs. At 50 token events per second, this isn’t optional — it’s survival.

Lifecycle-aware components handle the complexity of concurrent operations. Tools have explicit state machines (running → completed/failed/cancelled). Agents have session state. Workers have budget caps. Everything has a defined lifecycle, and the UI reflects it.

Configuration as architecture enables portability. The 4-layer merge with schema validation means FlowKunda runs identically whether it’s a Docker container on a server or a standalone binary on a laptop. Zero code changes between deployment targets.

Markdown-based memory gives agents persistent context without a database. Each agent has access to a global memory file and per-session memory files — plain markdown that both humans and agents can read and write directly. It’s simple, inspectable, and version-controllable. No serialization layer, no query language, just files.

CLI-over-API continues to be the right bet. Every time Claude or Codex ships a new feature, FlowKunda gets it automatically. No SDK updates, no API migration, no waiting for wrapper libraries to catch up.

What This Means#

FlowKunda started as a tool to scratch an itch — running multiple AI agents without losing my mind. Three versions and 53 commits later, it’s something different: a platform where the architecture actively enables workflows that weren’t planned.

Quick Tools exist because the chat-first interface wasn’t enough. Git integration exists because agents need to commit their own work. Interactive prompts exist because agents need to ask questions. The monitoring dashboard exists because you can’t manage what you can’t see. Each feature emerged from using the system and hitting a wall.

The eight phases of v0.0.3 tell that story clearly. No grand unified plan. Just honest iteration: build, use, hit a wall, solve it, repeat. The architecture grew to meet real needs, not imagined ones.

That’s how 18,700 lines of code happen in five days. Not because you planned for 18,700 lines — but because each one solved a problem that was actually in front of you.

FlowKunda is open source. If you’re interested in multi-agent orchestration, check it out on GitHub.