System Prompt Token Optimization: Human-Readable vs Machine-Compressed Formats

When injecting large knowledge bases — project architecture, file maps, API references — into Claude’s system prompt, which format produces better results: structured markdown or compressed machine notation?

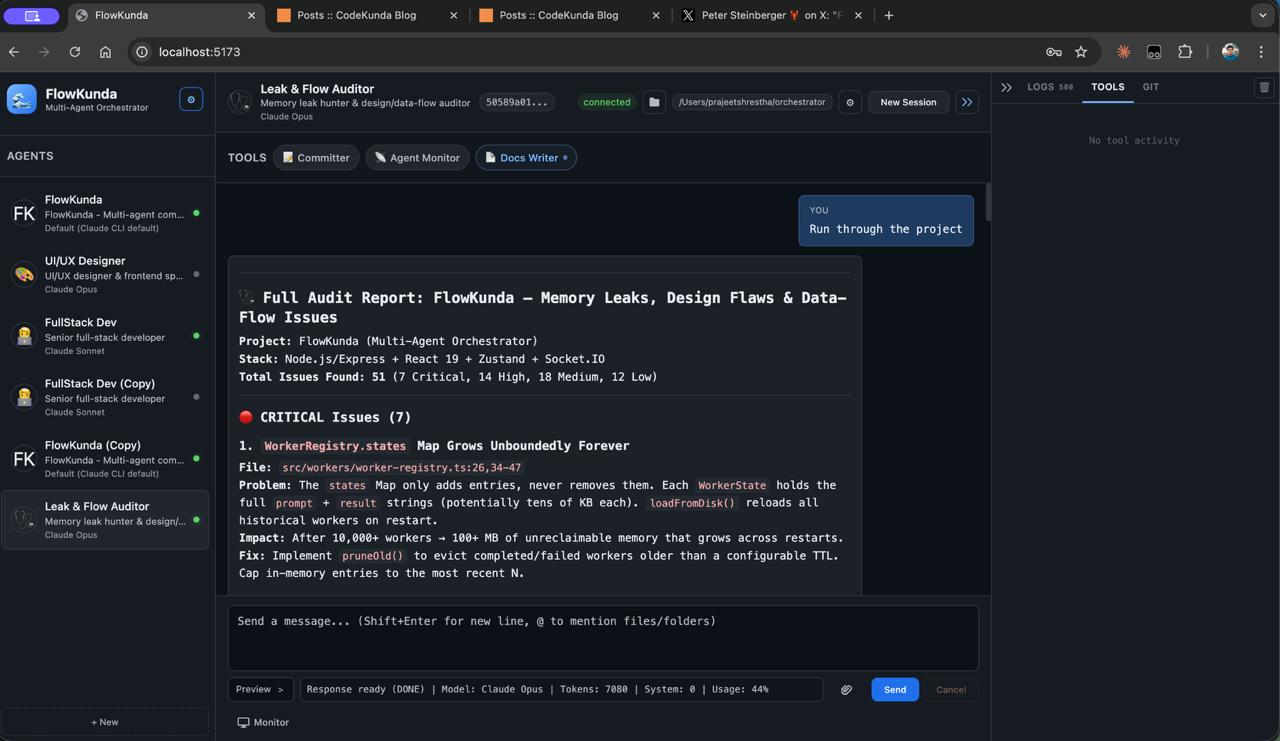

We built both as FlowKunda agent templates and analyzed them. The results changed how we think about prompt engineering.

The Two Formats#

Option A — Human-readable structured markdown:

## File Map

### Backend

`src/`

- `service/web-server.ts` — Express+Socket.IO, all WS events,

sessions map, monitor namespace. `startWebServer()`

- `service/session-manager.ts` — Per-agent session lifecycle,

message queue, Claude/Codex CLI spawn, streaming. `SessionManager`

Option B — Machine-compressed key=value notation:

FILES:BE:src/

s/web-server.ts=Express+SIO,WS events,sessions map,monitor ns;startWebServer()

s/session-manager.ts=per-agent session,msgQ,Claude/Codex spawn,streaming;SessionManager

The Data#

Raw Size#

| Metric | Markdown | Compressed | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characters | 11,416 | 7,445 | 35% |

| Words | 1,108 | 195 | 82% |

| Lines | 156 | 90 | 42% |

| Estimated tokens | ~4,499 | ~2,492 | 45% |

At first glance, compressed looks like a clear win — 45% fewer tokens. But the story is more nuanced.

Character Composition#

| Category | Markdown | Compressed |

|---|---|---|

| Alphabetic | 72% | 80% |

| Punctuation | 17% | 16% |

| Whitespace | 10% | 3% |

| Chars per rough token | 2.5 | 3.0 |

The compressed format achieves higher information density (3.0 chars/token vs 2.5) but primarily from eliminating whitespace (10% → 3%), not from smarter encoding. Punctuation ratios are nearly identical — the compressed format just traded one set of delimiters (markdown: ##, **, `, - ) for another (=, ;, :).

Where the Savings Actually Come From#

We stripped formatting from the markdown version to isolate pure content:

| Savings Source | Characters Saved | % of Total Savings |

|---|---|---|

| Prose and whitespace removal | 3,214 | 81% |

| Formatting markup removal | 645 | 16% |

Abbreviations (s/ for service/, etc.) |

112 | 3% |

81% of the compressed format’s savings come from removing prose and whitespace — not from the notation system. The abbreviations contribute only 3%.

The Delimiter Surprise#

Both formats use structural delimiters. We counted them:

| Markdown | Compressed | |

|---|---|---|

: colons |

93 | 102 |

— em dashes |

56 | 0 |

| pipes |

36 | 55 |

= equals |

14 | 53 |

; semicolons |

3 | 17 |

| Total delimiters | 202 | 227 |

The compressed format uses more delimiter tokens (227 vs 202) despite being shorter overall. Each =, ;, | is typically 1 token in BPE. The compressed notation doesn’t save on structural overhead — it increases it by needing explicit delimiters to replace the whitespace and formatting that naturally separated concepts in markdown.

Markdown Formatting Overhead#

| Element | Count | Extra Tokens |

|---|---|---|

## / ### headers |

19 | ~19 |

**bold** pairs |

22 | ~44 |

`backtick` pairs |

181 | ~362 |

- bullets |

44 | ~44 |

| Total | ~469 tokens |

Real overhead — roughly 469 tokens on formatting. But these tokens serve a critical purpose: structural navigation. Headers act as section indices. Backticks delineate code identifiers from prose. Bullets create scannable lists.

How BPE Tokenization Actually Works#

Claude uses a Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer trained predominantly on natural language, code, and markdown documentation. This training distribution matters enormously.

Natural Language Advantages#

BPE tokenizers merge frequently-occurring byte sequences into single tokens during training. Because the training corpus is dominated by English prose, markdown, and code:

- Common words:

the,function,server,message→ 1 token each - Programming terms:

Socket,Express,session,worker→ 1 token each - Markdown patterns:

##,**,`→ well-known 1-token sequences - Natural phrases:

system prompt,file path→ 2-3 tokens (close to word count)

Where Compression Hurts#

Dense notation like s/web-server.ts=Express+SIO,WS events,sessions map,monitor ns;startWebServer() creates patterns the tokenizer has never seen:

-

Novel byte sequences:

s/webisn’t a common training pattern. The tokenizer likely splits it ass+/+web= 3 tokens.service/webis alsoservice+/+web= 3 tokens. No savings. -

Ambiguous abbreviations:

SIOcould mean anything. The model must spend inference compute mapping it to Socket.IO.Socket.IOmaps directly to the concept. -

Mixed delimiter semantics: When

:,=,;,,, and|all serve different structural roles in a single block, the model must infer the grammar before using the information. In markdown, the grammar is pre-learned. -

Lost structural hierarchy: Markdown headers create a navigable tree.

SECTION:key=val,val;key=valis flat — the model must parse linearly.

The Chars-Per-Token Trap#

The compressed format’s 3.0 chars/token vs markdown’s 2.5 chars/token seems better. It’s misleading:

- The higher ratio comes from eliminating whitespace, not better token packing

- Whitespace in BPE is often merged with adjacent tokens (

the= 1 token, not 2) - “Removing” whitespace often doesn’t save tokens — it just makes remaining tokens harder to parse

- Punctuation-heavy compressed text generates more single-character tokens, lowering effective information density

The Hidden Cost: Inference Compute#

Token count is only half the equation. The other half is how much compute the model spends understanding the prompt before it can use it.

When Claude encounters s/session-manager.ts=per-agent session,msgQ,Claude/Codex spawn,streaming;SessionManager, it needs to:

- Recognize

s/as an abbreviation forservice/ - Parse

=as “purpose is” - Parse

,as “and also” - Parse

;as “key export is” - Map

msgQto “message queue” - Reconstruct the full mental model

When it encounters `service/session-manager.ts` — Per-agent session lifecycle, message queue, Claude/Codex CLI spawn, streaming. `SessionManager`, steps 1-5 are unnecessary. The information is immediately available in a format the model was trained on.

The Training Distribution Argument#

Claude was trained on billions of tokens of:

- Markdown documentation (GitHub READMEs, docs sites)

- Natural language technical writing

- Code with comments

- API documentation

It was not trained on billions of tokens of:

KEY=val,val;valcompressed notation- Custom abbreviation systems

- Dense delimiter-separated data formats

Using a format the model hasn’t been trained on is fighting the tokenizer AND the model’s learned representations.

What Actually Works#

Techniques ranked by effectiveness:

High Impact#

1. Remove prose and filler words (81% of savings)

- Bad: “The MCP server is the critical bridge that lets external Claude instances communicate with and control FlowKunda’s worker pool.”

- Good: “MCP Server — bridge for external Claude instances to control FlowKunda’s worker pool via stdio.”

2. Use terse descriptions, not sentences

- Bad: “This file handles per-agent session lifecycle. It manages the message queue, spawns Claude and Codex CLI processes, and provides streaming token output.”

- Good: “Per-agent session lifecycle, message queue, Claude/Codex CLI spawn, streaming.”

3. Eliminate redundant information — don’t explain what REST is. Don’t repeat architecture in the session management section. The model knows.

4. Use lists over paragraphs — lists eliminate transition words (“Additionally”, “Furthermore”, “In this case”).

Medium Impact#

5. Reduce unnecessary markdown formatting — keep ## headers for navigation, skip **bold** for emphasis, use backticks only for code identifiers.

6. Group related information — listing all REST endpoints as a single block rather than by category reduces per-entry overhead.

Low Impact (Don’t Bother)#

7. Abbreviating words (3% of savings, adds parsing cost) — service/ → s/ saves ~1 token but adds ambiguity.

8. Removing all whitespace — the model was trained on formatted text. Dense blobs fight the training distribution.

9. Custom notation systems (net negative) — KEY=val;val forces the model to learn your grammar before using your content. Any tokens saved are spent on parsing.

Referencing External Context Effectively#

Token optimization isn’t just about format — it’s about what you put in the system prompt and how you point the model at external knowledge. Files, code, and web sources each have optimal referencing patterns.

Referencing Files#

Don’t dump entire files into the system prompt. Instead, reference them with enough context for the model to know when and how to use them:

Bad — full file content inline:

Here is the entire web-server.ts file:

[400 lines of code]

Good — structural reference with key exports:

## Key Files

- `src/service/web-server.ts` — Express + Socket.IO server.

Exports `startWebServer(port)`. Handles namespaces: `/` (chat),

`/monitor` (dashboard). Routes defined inline, not split.

When to inline vs reference:

- Inline small, critical snippets (< 30 lines) that the model needs on every response — config schemas, type definitions, API contracts

- Reference by path + summary for everything else — the model can ask for the file or use tools to read it when needed

- Never inline generated files, test fixtures, or boilerplate — these burn tokens with near-zero value

Referencing Code Snippets#

When you do include code, context matters more than completeness:

Bad — raw code dump:

export class SessionManager {

private sessions: Map<string, Session> = new Map();

private queues: Map<string, MessageQueue> = new Map();

// ... 200 more lines

}

Good — annotated signature with behavior notes:

`SessionManager` (src/service/session-manager.ts)

- Manages per-agent Claude/Codex sessions

- `sendMessage(agentId, text)` — queues message, spawns CLI if no active session

- `resetSession(agentId)` — kills process, clears history, re-injects persona

- Sequential queue per agent — prevents session file race conditions

- Emits: `stream:token`, `stream:done`, `stream:error`

The model doesn’t need the implementation — it needs the interface and behavior contract. Include function signatures, event names, error modes, and constraints. Skip method bodies unless they contain non-obvious logic.

For type definitions, inline them — they’re high-value, low-token:

type ToolContext = "none" | "session";

type ToolStatus = "idle" | "running" | "completed" | "failed" | "cancelled";

Types are the most token-efficient code to include because they compress the entire behavioral contract into a few lines.

Referencing Web Sources and APIs#

For external APIs and web resources the model might need to interact with:

Bad — vague reference:

We use the GitHub API for repository management.

Bad — full API docs copy-pasted:

[2000 lines of GitHub REST API documentation]

Good — endpoint map with just what’s needed:

## GitHub API (used endpoints only)

Base: https://api.github.com

Auth: Bearer token in Authorization header

- `GET /repos/{owner}/{repo}` — repo metadata

- `GET /repos/{owner}/{repo}/contents/{path}` — file content (base64)

- `POST /repos/{owner}/{repo}/git/refs` — create branch

- `POST /repos/{owner}/{repo}/pulls` — create PR

Rate limit: 5000/hr authenticated. 403 with `X-RateLimit-Remaining: 0` when exceeded.

Only include endpoints the agent will actually call. Include auth patterns, rate limits, and error responses — these are the things the model can’t guess.

For web URLs as knowledge sources:

## Reference URLs

- Architecture decisions: https://docs.project.com/adr/

- API changelog: https://api.project.com/changelog (check before assuming endpoint behavior)

- Status page: https://status.project.com (check if API calls fail)

Give the model URLs it can fetch with tools when needed, rather than pre-loading content that might be stale. A URL + one-line description is ~10 tokens. The page content could be 5,000+.

The Reference Hierarchy#

Think of system prompt references in three tiers:

| Tier | What | Strategy | Token Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Always loaded | Type definitions, key interfaces, config schema, critical constraints | Inline in system prompt | Low (high value per token) |

| Indexed | File map, endpoint catalog, event names, error codes | Path + one-line summary in prompt | Medium (enables tool use) |

| On-demand | Full file contents, web pages, API responses, large datasets | URL or path only — model fetches when needed | Minimal |

The goal is to give the model a table of contents, not an encyclopedia. It should know what exists and where to find it, then pull details on demand.

The Bottom Line#

| Format | Chars | Est. Tokens | Comprehension Cost | Net Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original verbose prose | 26,419 | ~7,500 | Low | Poor (too many tokens) |

| Terse markdown | 11,416 | ~3,200 | Low | Best |

| Compressed notation | 7,445 | ~2,100 | High (parsing overhead) | Worse than it looks |

The sweet spot is terse natural language with structural markdown. You get most of the token savings (57% reduction from the original) without any comprehension penalty. Going further into compressed notation enters diminishing returns where parsing costs exceed token savings.

You’re optimizing for Claude’s comprehension budget, not just its token budget. A 3,200-token prompt the model instantly understands beats a 2,100-token prompt the model has to decode first.

This analysis came from building FlowKunda’s agent template system — optimizing the character field that gets injected as system prompts for Claude and Codex sessions. Read more about FlowKunda’s architecture.